Archive Dive: The Taco Truck And The Thrift Store

An appreciation of aging, vibrant suburbia

I first published this piece at Strong Towns in 2021, and have never published it at my newsletter, although I have quoted it or written similar pieces over the years. This is one of the few older pieces I still occasionally have people mention to me; it did the rounds among local urbanists and pedestrian advocates, and it feels like a good time to publish again.

The piece has been lightly edited, but is substantially the same piece, and I stand by every word of it.

Strong Towns material is published under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

I was driving around Maryland last week, and I stopped at a large thrift store near Wheaton-Glenmont in greater Silver Spring, a D.C. suburb in Montgomery County. This particular store began life in 1961 as a Towers Mart, a local discount chain, then became a Zayre, and finally an Ames (Zayre acquired it after Towers went bankrupt; Ames bought Zayre). Ames, one of the largest and longest-surviving of the Walmart competitors, gave up the ghost in 2002.

By the mid-2000s, retail had become both larger and more concentrated than it was in the postwar era. Stores of this size are not as common as they once were; hundreds of such buildings vacated in the 1990s and 2000s remained empty for years, sometimes decades. Some still sit empty.

This former Ames building sits on an odd parcel, with part of the parking lot built on a steep slope. It’s also, obviously, a pretty old building as box stores go. It’s too small for a Walmart or Target, which are largely built out anyway, and it’s too large for a supermarket or a “medium-box store” like a Dick’s, Petco, Barnes & Noble, or Best Buy.

The giant thrift store that occupies it now, which roughly imitates the layout and product range of a discount department store, is basically a perfect fit. It allows people in this crowded, deeply settled area to donate a lot of stuff that would otherwise end up in a landfill. And it provides cheap and often pretty good merchandise to the area’s less affluent residents. (It was also a fun diversion when I was a grad student in nearby College Park.)

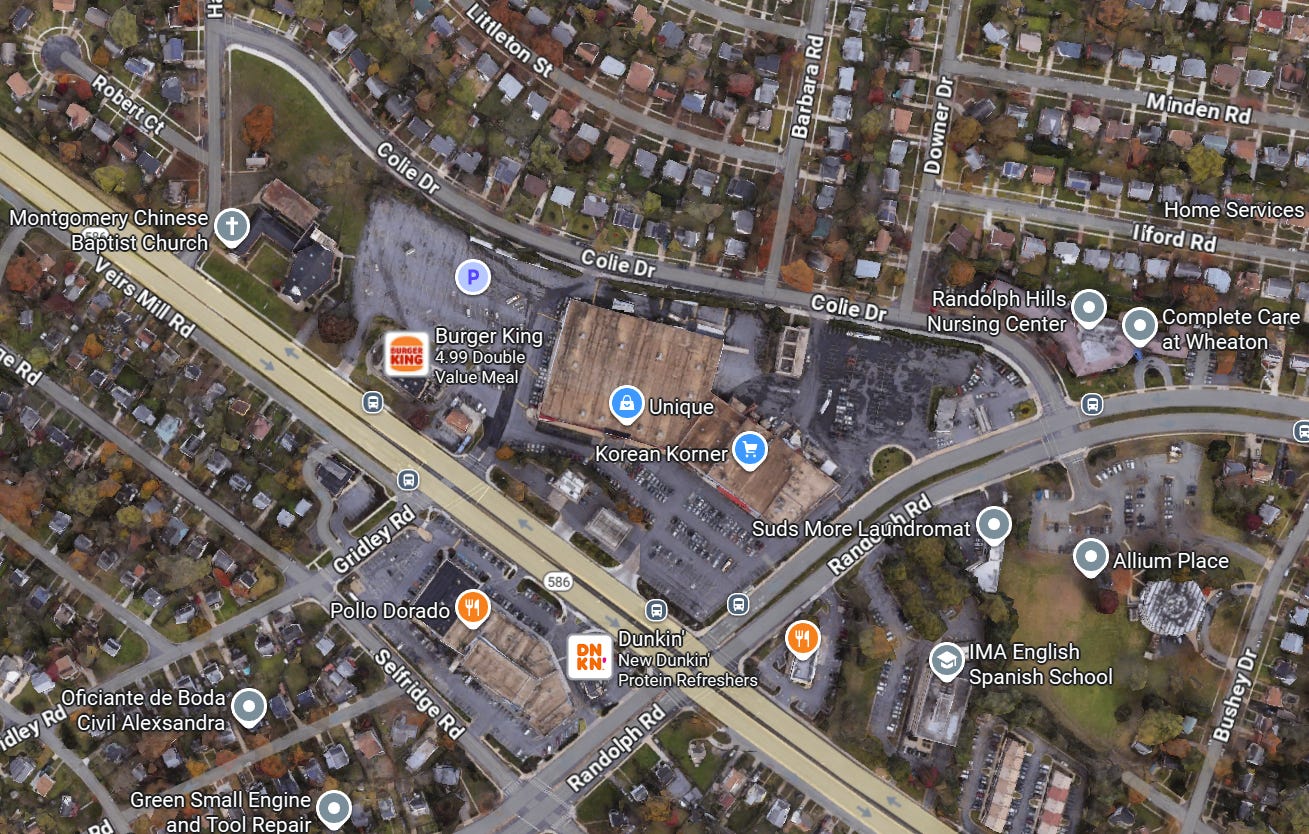

Here’s the satellite view of the strip plaza where the store is located:

And here’s a photo of the store’s cavernous interior. (The drop ceiling and exposed fluorescent lights scream “Ames” or “K-Mart”!)

Notice how many homes, mostly modest postwar construction, are within walking distance of the plaza, which also includes a small Korean-focused international supermarket. Also notice how it’s an island bounded by roads, including a six-lane stroad. What does that mean, in an area that’s trended a little more working-class over the decades? It means lots of pedestrians navigating a built environment that was designed for motoring.

It’s quite common in this area of Maryland to see food trucks or carts set up in parking lots—the space is freed up, either due to retail vacancies or to higher-than-planned pedestrian traffic—often selling Latino foods or snacks. In the overbuilt parking lot of the giant thrift store, there were not one, not two, but three food trucks, at least on the day I visited. (I was there too early for lunch and they still appeared to be setting up.)

Here’s the original 2021 photo:

And a photo I took just a couple of weeks ago:

How many such vendors are licensed and technically allowed to operate, in a strip mall parking lot no less? If the Washington, D.C., food truck scene is any indication, not all of them; Washington City Paper ran a March 2021 piece on the fight for business between flashy, licensed food trucks and their plainer, often unlicensed competitors.

In D.C., as in Maryland, most of these are Latino-owned and serve Latin American staples. It’s sometimes suggested that Latino immigrants tend to treat American strip plazas like Mexcian or Central American town squares; places to hang out or engage in small-scale commerce; spaces to be. By contrast, native-born Americans and particularly white suburbanites tend to regard strip plazas as places to go for specific, narrow reasons, and then leave. I’m sure this oversimplifies things, but it seems to hold some explanatory power.

This parking lot is apparently used for a few other things too, which I did not notice or were not set up when I was there, according to a Montgomery County-based transit activist, who said of it: “People use this parking lot for food trucks (with seating!), wholesale/retail vending of produce (coconuts, guavas, collard greens), religious services, and car repair, in addition to parking. If only more parking lots were like that.”

For something similar, take a look at this row of repurposed multifamily houses, now various offices and businesses, in the relatively poor and heavily immigrant community of Langley Park, about 20 minutes away.

Langley Park suffers even more intensely from the dynamic of heavy pedestrian traffic in a working-class and largely carless community originally designed for the motoring middle class.

This isn’t aesthetically pleasing, really. In fact, it’s the kind of environment that, growing up in quiet, affluent, white suburbia, you instinctively learn to avoid. In some cases, though, there’s no fear or trepidation going on; there’s just no particular reason to go to these places. This isn’t to glorify it either; this community does have an elevated rate of poverty, dangerous highways, lots of traffic, and a very old housing stock. (The Purple Line, which is inching towards completion, may bring some much-needed investment to this landscape, and maybe also gentrification.)

But while I might once have just seen run-down buildings through my windshield and kept on driving, now I see people doing what they can with what they have. It’s not perfect. They don’t think it’s perfect. But it’s better than abandonment and blight. Many hold the impression that the working-class immigrants who often own and patronize these businesses are to blame for the physical decay. But they’re simply buying or renting what’s available, often from commercial landlords who are speculating on the land.

What’s more, suburbia doesn’t physically age well. Most of the structures along here, and many throughout the whole area, are well past their “design life.” I see people trying to make this landscape into something better, something it wasn’t designed for, and to find a way to blame them for its shortcomings strikes me as cruel. If it didn’t look like this, what would it look like? Not like how it began. That’s baked into it from the start.

There’s a tendency to view this kind of informal reuse of once-pristine suburban landscapes as sort of akin to “downcycling,” a term that denotes the reuse of something in an inferior manner to its original use. It codes as decline, poverty, disinvestment. It suggests crime. Or maybe just a little bit of unchosen and occasionally fraught human interaction, like busking or begging. Or unlicensed food carts.

We’ve come to have a low tolerance for chaos and disorder. We expect things to be neat, organized, clean, frictionless. This expectation is ironic, because we glorify our country’s rough-and-tumble entrepreneurial history, yet we often look down on people who embody it today, and on the commercial landscapes that result.

Back in 2019, I attended Charles Marohn’s Strong Towns book talk, fittingly in the nearby D.C. suburb of Greenbelt, Maryland. He may not have used the word “chaos,” but he argued that affluent suburbanites were basically wrong in their expectation that we were rich enough to buy our way out of that rough and tumble, the need to be constantly productive, and the certain messiness that comes with it. In reality, it’s more like we’re living on accumulated capital that we’re no longer producing.

This understanding is now a part of my everyday perception. I hope others can see things like this differently, too. And next time, I’ll go thrifting at lunch time and try the tacos.

Related Reading:

Don’t Patch The Hole In The Wall

Thank you for reading! Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter. You’ll get a weekly subscribers-only piece, plus full access to the archive: over 1,500 pieces and growing. And you’ll help ensure more like this!

Many 'affluent' shoppers also enjoy thrift stores and other opportunities for inexpensive exchange of services and goods, including clothing swaps, neighborhood kitchens, etc. The many 'second-hand' stores in our city appeal to a wide range of folks with varying incomes - working people, students and young people, tech and biotech employees, retirees, etc. Some stores are highly curated. One store is owned by a non-profit dedicated to hiring and training young people. It sells a wide variety of good quallity second hand items, including books, dishware, luggage, clothing, artwork.