Sacramentalism And Consumerism

How to think about too much stuff

Readers: Every full week before Christmas, I publish a series of longer, fuller pieces, and offer a discount for new yearly paid subscribers (newly signing up or upgrading from free). This week is no different. The new-subscriber discount runs until the end of Sunday, the 21st. If you’ve been on the fence about upgrading to a paid subscription, this is a great time. Your support keeps this going. Here’s to a sixth year of The Deleted Scenes!

When I think about memories and nostalgia, I think about the idea of sacraments. In Catholicism, at least, a sacrament is a “visible sign of an invisible grace.” Not just a sign of grace, but a physical, worldly ritual which conveys that grace. They’re not merely symbolic; there’s no baptism without water. (Well, there is, but I’m not writing about theology here.)

My point here is to make an analogy: the idea of some ordinary thing in the world—water, bread—conveying the divine feels to me like a “higher” version of the way memory and nostalgia work. Often, you forget things unless you go looking through a box of keepsakes, for example. Or unless you physically revisit a place. That’s part of why decluttering is difficult: it feels like getting rid of the visible signs of many invisible parts of your life, your mind.

In a real way, decluttering is about choosing which memories you are willing to potentially never be able to experience again. It is about choosing to delete a certain fraction of your life. In a less real way, it is like killing a part of yourself. Or perhaps pruning, which is and isn’t the same thing.

I was thinking about all this again because I was going through a bunch of stuff at my parents’ house recently (I had some thoughts here about garage sales as “consumer archaeology”). What’s wild to me is how much I remembered, going through this stuff, from a time in my life that I’m old enough to start forgetting now.

It’s remarkable how much the brain can retain when prompted. (Oh, I bought that on eBay, and I got a half-off refund because the guy spilled perfume on it and it wasn’t in the description. That was from that house where the lady didn’t want to sell her broken camera for $5, remember her? This was the last garage sale we went to before I started my junior year. Etc., etc.)

Some of the things I found were interesting. I don’t remember quite a lot of them. There was a shell of a Sony Walkman—it started as a Sony Walkman, but it didn’t work, and we’d kept the very nice-looking shell in case we ever found a working model in poor cosmetic condition. (We didn’t. But do you think I threw out the shell?)

There was this rare (though probably worthless, and unfortunately broken) clock radio using a keypad for the direct entry of alarm times:

GE made a handful of programmable clock radios in the early 80s, and this was probably a poor imitation (the GE models were really cool and looked like early home computers). In terms of any history of clock radios that might exist, this little store-brand model might not even be in there. A true undocumented little piece of history for a consumer product that once ruled store shelves!

There were these floppy disks with a gold and black oval logo that made me think to myself, “Quick Robin, grab the Bat-Floppies!”

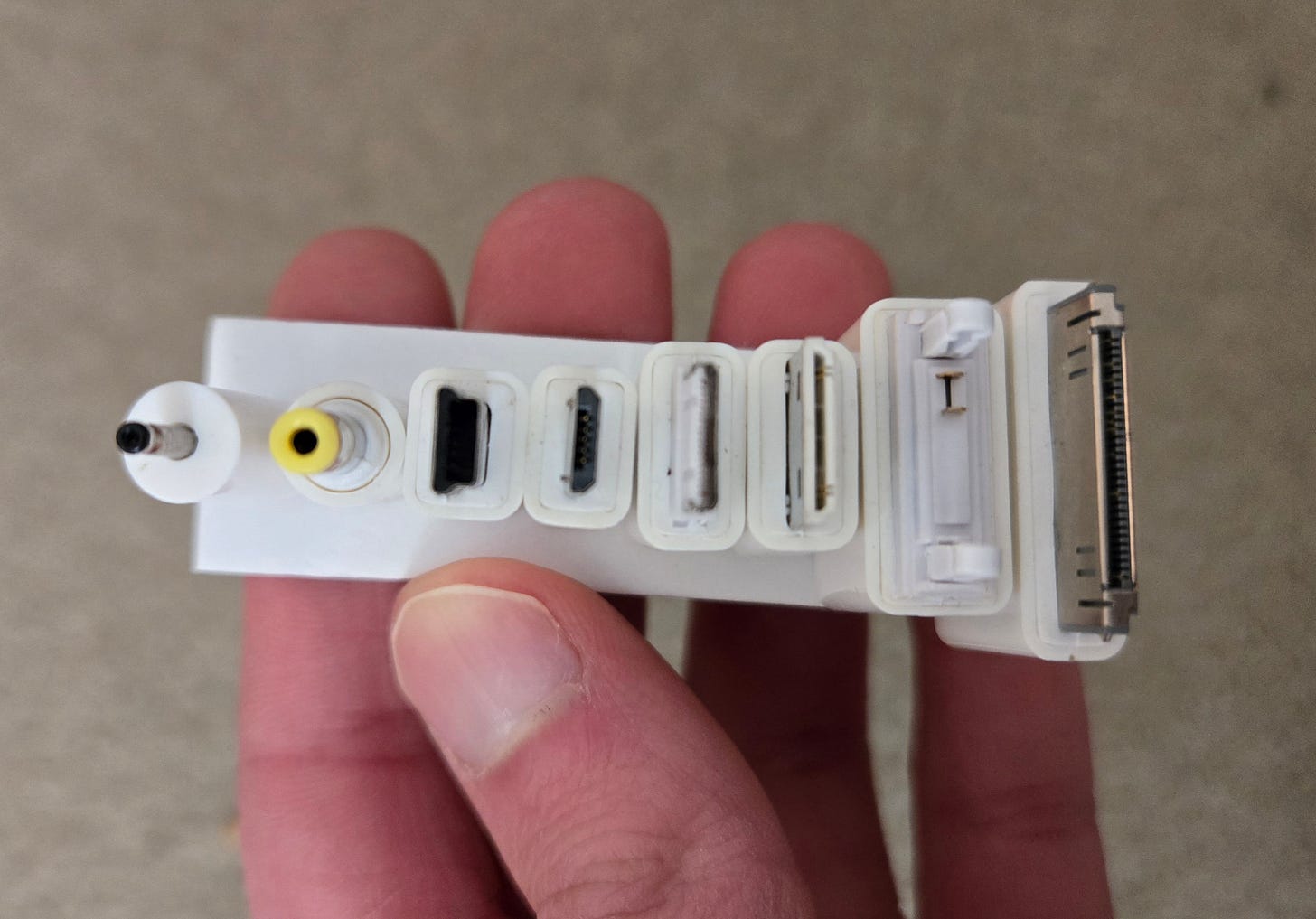

This neat power bank with a bunch of different plugs is now largely obsolete because most of these plugs aren’t used anymore. Finally Apple got on board and switched their typical charging plug to a USB variant, USB-C, which is commonly used today on PCs and Android phones and tablets (and even the Nintendo Switch).

There was also some stuff I actually wanted to keep, like some fun retro video games. (I might actually like the Sega Genesis better than the Super Nintendo. At least as I’m writing this.)

It’s a nostalgia trip, but it’s also sort of dismaying, in a way. I remember when I was in high school and college, and I had a lot of spare time, and this curious old consumer stuff seemed like a big part of the world. I guess it’s sort of like Toy Story—you imperceptibly leave things behind, and suddenly you aren’t quite the same person you were, and the stuff doesn’t capture your imagination in the same way.

That’s the slightly spooky thing about going through stuff—you almost feel like a ghost rummaging through a dead person’s junk, only the dead person is the version of yourself that you imperceptibly but inexorably stopped being.

There’s almost a kind of superstition at play here: if I never go through this stuff, I won’t age. Perhaps I’ve overly abstracted that sacramental idea, to the point of really almost believing that physical stuff can make present, anamnesis-like, the moment in our life from which it hails. But that’s a recipe not only for something like idolatry—nostalgia as a god—but also a recipe for overlooking the present, for conjuring old memories instead of making new ones.

The other part of why I kept some of these things all these years, like the broken programmable clock radio, is because I had a frankly pretty inflated idea of how important collecting old stuff was. I thought of it—back when it was a fun diversion from studying my SAT or GRE or whatever, when I had no real responsibilities—as documenting history. As preserving the emblems of a lost time.

Even then, I think, I had this “sacramental” view of anti-consumerism. These old, forgotten consumer products were the ways we could remember an older, better version of our society. I was Winston Smith rescuing the old paperweight from the junk shop; I was a monk laboriously preserving civilization as it collapsed around me.

Looking back, it’s rather funny how little being in college, or thinking about a career path, actually weighed on me or took up my mental energy. I was also quite an environmentalist, and part of this all, for me, was resisting consumerism, being thrifty, not throwing things away if they still worked or could be made to work.

I think I believed that people threw things away because they hated the environment or because they were selfish. I remember feeling proud of having a flip phone and a slow clunky laptop, unlike those greedy people with their stupid iPhones and “aluminum unibody” MacBooks that couldn’t be repaired. I remember making unwarranted connections, like finding “smashing” videos on YouTube where guys would buy some expensive new device and then smash it (I suppose they made the money back through video revenues?) and imagining that everyone who bought new stuff was like that. At least the crazy guys were being honest.

A little diversion here: if you follow progressive political commentary, one point you’ll see raised a lot is that conservatives often conflate “random lefty on social media” with “the Democratic Party establishment.” The reason conservatives do that, I suppose, is that they think the online crazies are being honest about the agenda, and the party officials are not.

Often progressives will blame the right-wing media for playing these games of telephone with left-leaning policy ideas, finding one extreme-sounding person and using them as a stand-in for “the left,” etc. I know how that works, and that is part of what’s going on with political polarization.

But it’s interesting to me how—all on my own and with an issue that wasn’t really left/right—I did exactly the same thing: Moron who smashes iPhones for views on YouTube is really everyone who buys a new smartphone. You can definitely motivate yourself into motivated reasoning on many topics. Diversion over.

Part of growing up, I suppose, is leaving some of this stuff behind. One of the challenges of doing that is that it forces you to rethink a lot of ideas that you’ve built into your sense of yourself and the world. I find it difficult to just make an exception to my environmentalist tendency, even now, and say “Yes I care about wastefulness and consumerism, but let’s just toss this empty Walkman shell.”

Instead, because I want to be consistent, throwing one thing away makes me say, “Eh, I guess throwing stuff away doesn’t matter, screw that sappy environmentalism! Let’s throw more stuff away! Hell, let’s smash it first! It’s just stuff!” But then you subtly absorb the damage of violating your principles. You keep the stupid Walkman shell, like a useless totem, a communion wafer without a priest, or you immolate your worldview.

Maybe this is all a kind of pridefulness, or a lack of real priorities. I imagine at some point, it all just recedes too far into the past to care about, and it all just becomes clutter to be swept away. You thought you were holding onto keepsakes and memories and that your life resided in your things. Meanwhile they were moldering away, doing nothing but aging.

That’s the decision you see people making when you go to estate sales. Talk about going through stuff being spooky! I remember so many estate sales where an entire, deeply inhabited house was just completely for sale. Literally everything that wasn’t nailed down was for sale. I’ve even seen the half-used contents of kitchen pantries for sale. (A dime for half a pound of macaroni ain’t bad, I guess?)

You’d be rifling through someone’s desk or looking in a kids’ cabinet set, trying to find a video game or some cool old thing, with even odds that some poor guy kicked the bucket in the king bed behind you, which is also for sale, or that some other tragedy—or maybe an opportunity worth blowing up their physical life—befell the family.

What could drive a person to sell the literal contents of their cabinets and drawers? How could they…expose the whole accumulated body of stuff that constituted their life—or the life of someone dear to them—to a bunch of guys looking for a deal, like the scoundrels pulling down Scrooge’s curtains while his possible-future self lay dead in the room?

I guess when I found neat stuff at these sales, I always felt like I was the almost-wrongful beneficiary of a person’s wrongful tossing away of their home. I was complicit in a kind of crime, or at least I was being a voyeur. But I suppose that’s just me reading sentimentalism into it. And I suppose this notion sacramentality is ill-applied to so much junk that is someone else’s cast-offs, only a tiny fraction of which was ever of interest to me anyway. All of this meta-thinking is a big part of why it’s difficult to get rid of things—either your old stuff, or your old ideas.

But moving on from a collection of things isn’t moving on from your life; it can be getting back to your life, by clearing out mental clutter. It’s often recapturing the feelings and experiences in real life that this accumulated stuff merely represents. If ordinary objects are sacramental, it is only in the barest sense: not conveyances of anything, but mere empty symbols, gesturing fruitlessly at what they signify but do not make present.

This futile drive to pin down a dynamic, passing moment in life is also the animating impulse behind NIMBYism. It is, ultimately, a metaphysical error: a denial of death.

Jesus said “Where your treasure is, there your heart will be also.” There was no exception for neat old stuff acquired at a garage sale. But “treasure” can be more than stuff; it can be a moment in time which is over. It can mean a conception of neighborhood character which no longer exists except as history. How much do we deny ourselves, trying to grab onto water and miss the beauty of the stream?

To deny death is to live in the past. But the past cannot be dwelt in. We, as people and as communities, only grow and mature, only build places worthy of passing on, when we accept that all things must pass.

Related Reading:

Gift Shops Are A Pleasant Step Back In Time

Home Consoles Changed What Video Games Were

Thank you for reading! Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter, discounted just this week! You’ll get a weekly subscribers-only piece, plus full access to the archive: over 1,400 pieces and growing. And you’ll help ensure more like this!

This hits home for me after going through my storage unit when returning from Estonia after seven years. One example. I couldn't believe the poor quality pots and pans I cooked with in my early 20s. I had less disposable income in those days, but I still spent money--just not on kitchen stuff. Most of it went straight in the trash, but the 1980s Revere Ware copper bottom pot, the first pot I ever cooked with as a child, I couldn't bring myself to part with. I realize this is silly. There's no reason to keep it other than nostalgia of childhood. I don't enjoy cooking with it, but the fact that I've held onto it for so long, makes it even harder to part with.

Another unrelated example. For about ten years I had the same tote bag I used for work, international travel, etc. That bag traveled everywhere with me, and it was more than showing its age. I found a mint condition replacement on eBay for $25. When I got the new one, I threw the old one away, since it was so worn out that I don't think anyone would want it second hand. The one I purchased on eBay is identical, so I forget it's not the same one. It serves the same purpose, stirs the same memories. Every once in awhile, I'll remember that that the "real" one is somewhere in a landfill and it makes me uneasy. I realize this is irrational, but psychological attachment to items is real.

"Often progressives will blame the right-wing media for playing these games of telephone with left-leaning policy ideas, finding one extreme-sounding person and using them as a stand-in for “the left,” etc. I know how that works, and that is part of what’s going on with political polarization."

Ironically, I think this often has the effect of driving social change.

Conservatives do this to drive outrage on their side, which is a very active motivator.

But by doing so, they drive the idea into the national spotlight and cause it to be talked about.

And with how polarized we are, it suddenly becomes a cause célèbre for folks on the left, who feel compelled to rally around it since it's under attack, even if it's only loosely affiliated with their own personal ideas.

The end result is that this thing that nobody had heard about a week ago is now suddenly supported by half the country.

It's quite fascinating to watch.

I can't think of a similar example happening on the right only because the dynamics for them are different. The two sides aren't symmetrical, after all. If you can think of one, let me know, though.