A First Impression

Meandering museum thoughts

I had (what I thought was) an interesting question last weekend, looking at the French impressionism section of the National Gallery of Art. (Thank God for the end of the shutdown and the reopening of the Smithsonian museums!)

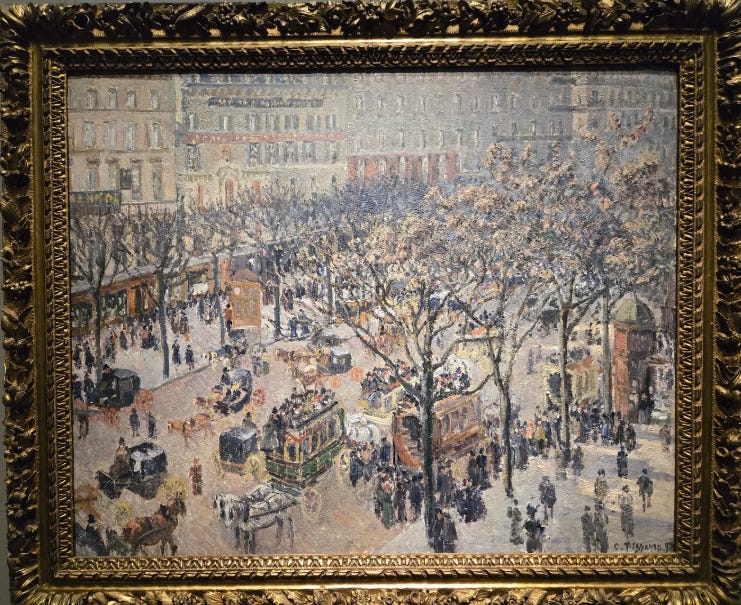

Take a look at these three, which I particularly liked:

My question is: why is it that these paintings in some ways look more “real” than photorealistic paintings? How does a style so obviously not aiming for literal realism capture the feel of what things really look like?

The last time we were at the Gallery, last year, we caught a tour in this section. The guide was talking about how at the time, traditionalists considered impressionism to be crude, newfangled, not real art, etc. Some of them described it as absurd, as a tasteless departure from the rules of painting.

What made me really curious about that was not that art critics were basically Cranky Kong1, but that impressionism looked, to critics at the time, like a departure or a break from the long evolution of standard, classical art. And yet, looking back, impressionism very much looks like one variety within a broadly classical body of styles. Perhaps it was heresy, but it was not apostasy.

The generation of styles after impressionism—whatever we now call modern art—seems to be where a true break occurred, an entire style(s) without obvious reference to or observance of almost all the old rules, or to what things actually look like. It wasn’t just employing different answers, it wasn’t even asking the same question.

This reminded me of something else: art deco, in architecture. Art deco was very much a modern style, and was seen as a break with tradition. But it also paid considerable homage to classical styles of architecture. Perhaps it looked jarring at the time, but again, from today’s vantage point, art deco fits perfectly into the slow, organic evolution of “traditional” styles, so much so that like impression, it kind of obviously looks like the last classical style before the break. Brutalism, and what gets called “modernism” in general, would be the point of departure.

Perhaps the same general phenomenon applies to the old streetcar suburbs, which a lot of people today view as one variety of urbanism, and which was probably the last variety we ever built at scale, but which at the time were, well, suburban.

It’s fascinating that the question “Does this style fit into, or break with, the styles that precede it?” is not a precisely answerable question of fact. You could say that the people closer in time to these innovations couldn’t really see what they were looking at, that the differences were too glaringly obvious for them to see the continuities.

Or, you could argue that looking back, we like to tell stories and smooth over frictions, and so we imagine a body or evolution of traditional styles that really had very little to do with each other. We stitch the randomness of the actual past into the story we call “history.”

How much of this is reality, and how much is perception? And how do we know whose perception is closer to reality?

But our main museum of the day was the Air and Space Museum. I wrote about the one in Chantilly, which, frankly, is a lot more impressive, though a lot sparser in terms of information and context. It’s probably better for kids, or anybody who gets antsy reading card after card after card with a little artifact in between to keep you engaged, like a pittance from a slot machine.

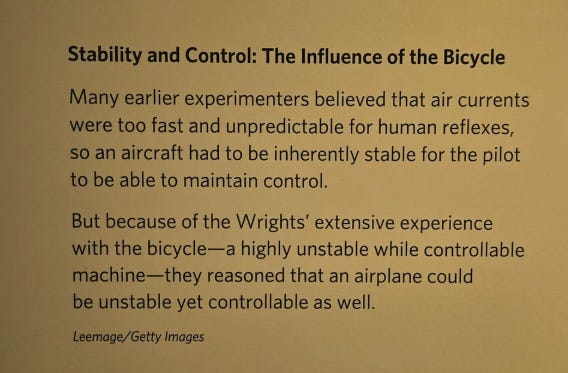

The thing that strikes me about museums having to do with technology is how physical and mechanical everything was, and how that was a kind of psychological entry point for learning about the world. You see it with the origins of airplanes; the Wright brothers famously applied some of their mechanical knowledge of bicycles to the engineering problem of flight:

Obviously these guys were very smart and very dedicated. And America having a huge industrial ecosystem made a lot of this sort of thing possible. But in a way…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Deleted Scenes to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.