Continuity And Change In Silver Spring, Maryland

What Do You Think You're Looking At? #247

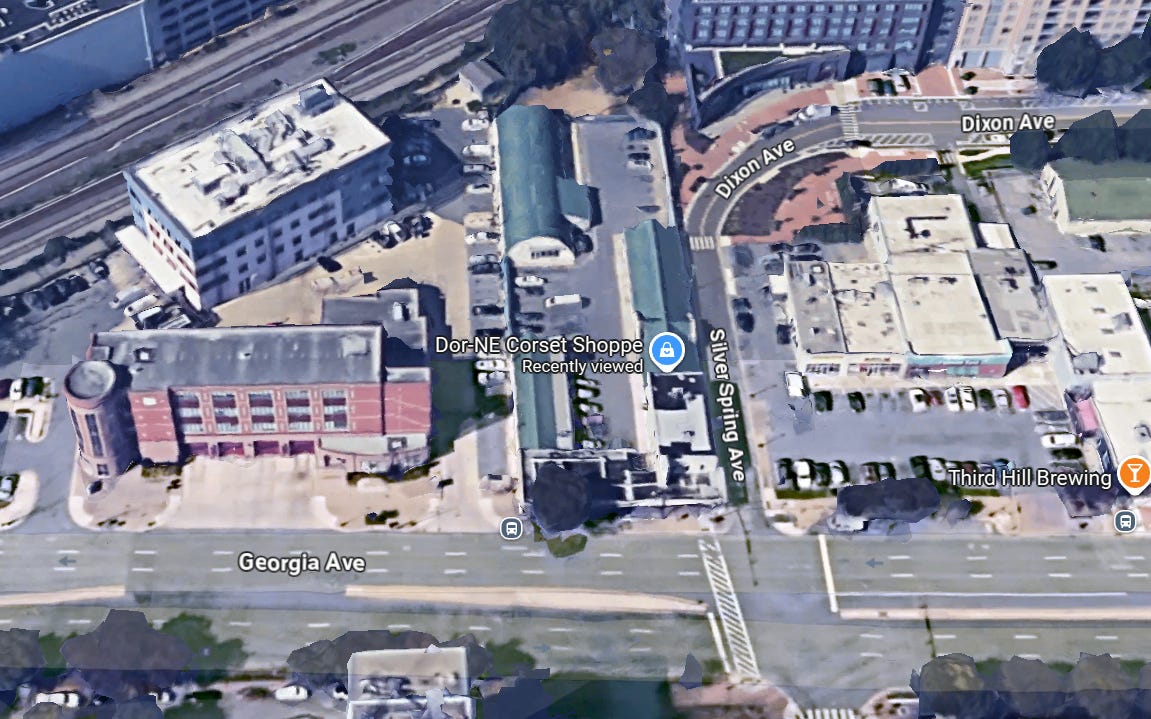

Last week I wrote about a store in Silver Spring, Maryland: Dor-Ne Corset Shoppe. It first opened in 1932, in Washington, D.C., migrated to Silver Spring, Maryland in the early 2000s, and is now closing.

I was struck by how long that actually is—nearly a century—and by how much of America’s urban history is told by that story. It’s a store that predates urban renewal and suburbia, and nearly predates widespread car ownership. Then it continues with a move to an older, fairly urbanized D.C. suburb, at a time when a lot of old shops were closing. The early 2000s were the peak of the Walmart panic, and quite a lot of shops that could trace their history back to an old downtown closed in that time. Check out that piece.

Today, I’m returning to the building that the Dor-Ne shop is in. The building itself is quite interesting, and is one of those examples of iterative development that can make a place just a little bit unique and give it a bit of whimsy.

I think people notice the absence of this in new development. Newer, larger buildings can have a blankness and blandness to them. Some of that is simply that they’re new, and time will fill in some of that sense of “texture,” of history, of the quirks of habitation. But some of it is the design and the scale.

When I write about “urbanism,” I include a place like Silver Spring, which is an evolving small city as well as an old suburb. And I include the uses and reuses of structures like this, as well as the redevelopment of old parcels into uses which are more befitting what the place has become in the present day.

Anyway. The building that Dor-Ne is located in is a two-story brick building, much like those found in most old downtowns/Main Streets. According to official Maryland property records, the structure was built in 1951. We will come back to that.

Here it is. From the front. Notice how you’re seeing what are really two buildings, with an overhang over the parking lot entrance connecting them.

From the side:

Standing in the interior parking lot, looking at the street:

Same position, looking away from the street:

And finally, looking again at the street from the far end of the parking lot:

As you can see, this is a small shopping center which is a mashup of the brick two-story building and some other structures, which form a rough u-shape, with the inner courtyard area being a private parking lot.

Now I had a hunch, based on that concrete pillar above the sign in the first photo, that the Dor-Ne building may have been an early supermarket. Kind of like this one (an old Acme), in Lambertville, New Jersey:

Or this one, a former Safeway, in Annandale, Virginia (it was a Bank of America for many years, and is now a Korean restaurant):

For whatever reason, the tall pillar was a common supermarket motif, so you can spot former, early supermarkets by this feature.

It’s also a pretty curious-looking complex overall; the two-story section with the corset shop has a little front area appended on; the rest of the little strip is one story. There’s also a warehouse-like structure in the back:

This is the kind of thing you get as old urban areas are incrementally worked on. It also seems pretty clear that the two-story brick structure predates the rest of the strip. Perhaps at one time there were other two-story structures here, and no parking lot.

So, what was it? My supermarket hunch was…wrong. It was, in fact, a hardware store!

Here, on a neat historic plaque outside the store, is a photo of the hardware store, taken in 1952:

Huh. So the brick structure is from 1925 (at least some of those star anchors are still there!) The expanded front and awning must have been completed in 1951, superseding 1925 in the official property record, even though the bulk of the structure is older.

The small strip of stores to the left would appear even newer, since that overhang looks freestanding here. That overhang, or more likely a new one, ended up being the roof of the current-day strip to the left of the original building.

And that warehouse-looking Quonset building in the back of the parking lot is also from this period. From the Silver Spring Historical Society, an excellent resource for this kind of thing:

IN 1945, JOHN H. HUNTER SOLD HIS HARDWARE BUSINESS to Lawrence B. Maloney, Sr., a former International Harvester Co. branch manager from Richmond, Va. Maloney was assisted in his new position by sons Lawrence (Larry), Jr. and Leonard. Renamed Maloney’s, Inc., the business also became an authorized dealer for International Harvester, Inc.’s trucks, tractors, and appliances.

Business expanded in 1946 with construction of a steel Quonset-style hut from which Maloney’s truck parts and service department operated. Butler Manufacturing Co. of Kansas City, Mo. manufactured the structure. Maloney’s Building Co. Division served as Butler’s local representative. The remodeled hut behind the store is actively used today.

The store began as Hunter Hardware, and the business itself actually goes all the way back to 1912. It was originally in a wooden building, which was torn down in 1925 for the current brick building, which stood freely before the front and overhang were added.

Here are more historic photos of the property.

The store eventually closed in 1984, and Dor-Ne moved into it in 2001, at which time it had become a shopping center:

Since Leshchiner moved her shop almost four months ago from F Street in the District to a nearly empty shopping center on Georgia Avenue, barely a mile from the city line, business has been brisk and she expects to do even better than the $500,000 she earned last year….

Dor-Ne sits in a shopping center at 8126 Georgia Ave. that is being renovated. Workers are tearing down walls and putting in electricity to turn other empty storefronts into rentable space for new restaurants, a cleaners and boutiques. A few doors down is a music shop. Across the street, mechanics fix transmissions and firefighters hang out in front of their station, next to a well-established flower shop.

What a neat little story.

This building illustrates something curious about arguments over development. Historic structures are often perceived or experienced as symbols of stability or nostalgia. We think of them—or perhaps it isn’t thinking so much as feeling—as having always been there, as defining what the place itself is.

We think much less about the process by which the places we now deem historic came to exist in the first place. If the wood structure housing the first iteration of the hardware store had survived into the 1960s or 1970s, it would probably have been deemed historic and been preserved—or at least its demolition would have been an outrage. If the Quonset hut were proposed today, it would be denounced as a garish contrast with the charming brick building. But these things were done at a time when towns still grew dynamically, and so it is the successor structure and its additions which are now perceived as historic, with a kind of settledness and finality read back into that ever-changing past.

The rise of suburban sprawl and NIMBYism and historic preservation combined to arrest this dynamism, and so what we now consider to be “historic” is merely the moment in time where we diverged from actually growing and iterating on our existing communities.

This is not an argument against historic preservation, per se. It is an argument for treating what comes next as existing, in a sense; for understanding neighborhood character as a spirit of building things, in continuity with all of the change the current form of the neighborhood embodies.

There is so much lost and forgotten change and dynamism and energy to which our historic buildings and cities point. The curious thing is that in preserving the symbols of that energy, we have lost the energy itself. We have forgotten how or why the places we love exist.

Surely we can and should keep some of them around, at least. But just as important, or more, is learning how to build upon them and build more of them, again.

Related Reading:

I Live Here Because Of Winn-Dixie

Why Do So Many Companies Hate Their History?

Thank you for reading! Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help support this newsletter. You’ll get a weekly subscribers-only piece, plus full access to the archive: over 1,400 pieces and growing. And you’ll help ensure more like this!